Palestinian Women Photojournalists

Palestinian women started taking photographs of families and holy places, ceremonies and weddings, but ended up taking pictures of bodies of killed young children, shelled schools, and ruined homes.

Photojournalism in Palestine was considered a male dominated profession as is the case in almost all Middle Eastern countries, but Palestine has always been the first country within the Arab world to offer women the opportunity to be in the lead and to break old social moulds when it comes to pioneering work and education for women.

The difficult circumstances in Palestine facing journalists in the occupied West Bank and Gaza forced many media establishments to choose employing local journalists who know the nature of the area, besides minimizing the amount of risks reporters and photojournalists face when covering clashes between Israelis and Palestinians in the Gaza.

This Essay will focus on Palestinian women photojournalists working within the Palestinian territories; thus excluding hundreds of Palestinian women journalists who are working all over the world after their families became refugees, or forced to exile.

Early photography in Palestine

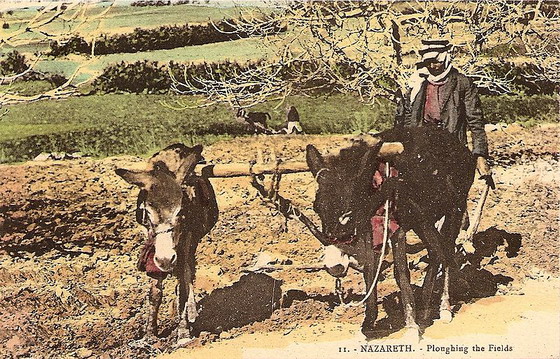

Photojournalism started after photography was introduced to Palestine in the late-nineteenth century by the British who undertook the first archaeological excavations in the Holy Land and tried to document their findings and the areas they investigated by pictures as Rachel Hallote reported (2007 pp 26-41). The British were followed by the Germans, and eventually by the Americans. Photography was introduced by people who came searching for evidence about biblical subjects and connections. Some elder Palestinians claimed that these excavations were part of a planned agenda to pave the way for the Jews to occupy Palestine well ahead the Nazi’s aggression on the European Jews. Americans were deeply involved in the archaeological photography in Palestine, but the British Palestine Exploration Fund dominated the photography activities in Palestine since the 1860s.

Photojournalism in Palestine is considered a male dominated profession as is the case in almost all Middle Eastern countries, but Palestine has always been the first country within the Arab world to offer women the opportunity to be in the lead to break old social moulds when it comes to pioneering work and education for women. As an example the first Arab woman to hold an academic title as a professor and to establish an institute in a western country was the Palestinian Kulthum Odeh (1892 -1965) as Tamimi (2008) reported.

During the same period another woman from the same city of Nazerath named Karimeh Abbud (1896-1955) was the first Palestinian woman to become a professional photographer. Karimeh lived and worked in Palestine in the first half of the twentieth century, research shows that she might have been the first female professional photographer not just in Palestine but in the entire East. Karima had her education in Nazareth, and at the Schmidt Girls School in Jerusalem, and the American University of Beirut in Lebanon.

Ahmed Mrowat (2007 p 72-78) reported that Abbud started photography in 1913 in Bethlehem after receiving a camera from her father as a gift for her 17th birthday. Her first photos were of family, friends and the landscape in Bethlehem. Her first signed picture available at present is dated October 1919. She started by setting up a home studio, earning money by taking photos of women, children, weddings and other ceremonies. She also took numerous photos of public spaces in Haifa, Nazareth, Bethlehem and Tiberias. When local Nazareth photographer Fadil Saba moved to Haifa 1930, Karimeh’s studio work was in high demand. The work she produced in that period was stamped in Arabic and English with the words: “Karimeh Abbud – Lady Photographer. She took photos of areas that have religious significance like Kafr Kanna in the Galilee associated with the Cana village where Jesus biblical stories claimed he turned water into wine. This village flourished in the 16th century, as it lay on the trade route between Egypt and Syria. Karimeh also took pictures of Mary’s Well near Nazareth or “The spring of the Virgin Mary”) which is reputed to be located at the site where the Angel Gabriel appeared to Mary and announced that she would bear a son. The well was positioned over an underground spring that served for centuries as a local watering hole for the Arab villagers.

In the mid-1930s, she began offering hand-painted copies of studio photographs. In a 1941 letter to her cousins, she expresses her desire to prepare a publicly printed album for her photographic work. According to Mrowat (2007) Karimeh ultimately returned to Nazareth, where she died in 1955. Original copies of her extensive portfolio have been collected together by Ahmed Mrowat, Director of the Nazareth Archives Project. In 2006, Boki Boazz, an Israeli antiquities collector, discovered over 400 original prints of Abbud’s in a home in the Qatamon quarter of Jerusalem that had been abandoned by its owners in 1948. Mrowat has expanded his collection by purchasing the photos from Boazz, many of which are signed by the artist.

While Palestinian male photojournalists started few years earlier than Karimeh as Nassar reported (2006 pp. 139-155) it was Yessayi Garabedian the leader of the Armenian Patriarchate in Jerusalem who started the first photographic workshop in Palestine. One of Garabedian’s pupils was the famous Garabed Krikorian as Ankori (2006 p36) reported that he established his photographic studio in the Old City of Jerusalem and worked in it from 1885 until 1948. Krikorian was entrusted to prepare the famous Sultan Abdul Hamid Albums on Palestine and later became the official photographer of Kaiser Wilhelm II during his visit to Palestine in 1899. Krikorian worked in his workshop for over forty years. His son Johannes travelled to Cologne in Germany to further his photographic training and came back after years of study and training to become the preeminent studio photographer in Jerusalem.

Another of Garabed’s students was Khalil Raad who opened his studio in 1890, across the street from the Krikorian studio, leading to intense competition between the two pioneering photographers. Peace was found when Raad’s niece, Najla Raad was betrothed to Johannes Krikorian and she became known as the peace bride. But unfortunately the historic photographic studio was tragically destroyed in 1948 by the Jews during their attacks on the city.

Palestinian women photojournalists now

I requested some information from The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics in the Palestinian Authorities for (2008) regarding the percentage of female Palestinian photojournalists registered officially, the Palestinian authorities statistics built its findings on ownership documents of photography studios showing that there are 201 Palestinian female photographers in the West Bank of a total of 984 photographers, 783 are males. This statistic was obtained from officially registered studios excluding the number of photographers in Gaza where it is difficult to obtain statistics by the Palestinian Authorities, besides there is a number of journalists who are not registered officially. A female photojournalist in Gaza Eman Mohammed explained to me the amount of social difficulty she faced for stepping in a male’s territory, she also expressed her determination to overcome obstacles as she said “going to take photos at invasions, airstrikes, violent demonstrations, and hot zones seemed like the only way to prove to everyone that I can handle this job, but I could never go there without getting verbally offended or harassed”.

Eman mentioned violent demonstrations, invasions, and airstrikes for her subjects unlike the subjects documented by Karimeh, because she had no other choices for such subjects are part of everyday life in Palestine. Should she had another choice maybe she would choose to take photos of fashion shows or festivals, art galleries or anything that is not related to death and destruction, but this is her city and this was the hard reality she had to face.

During the Visa pour l’image international photojournalism festival in Perpignan, France, from August 29 to September 11, 2005 Jack Crager (2005 p10, 15) reported that the exhibitions featured reflected individual photographers’ efforts to highlight major trends, during the exhibition all three participating Palestinian photographers’ images were of funerals in the Gaza Strip. Burgess (1994 p20-22) also reported that during the 1994 World Press Photo annual awards in Amsterdam, the top award went to Larry Towell’s image of Palestinian boys playing with guns for the camera. Palestinian photojournalists do not only witness and document attacks, they become sometimes part of such bigger picture. Smyth (2005 p12-14) wrote a feature article about three Palestinian photojournalists and brothers based in the Gaza strip who are employed by Reuters. Smyth reported that their work regularly takes them to scenes of chaos and destruction in which they are sometimes, inevitably, involved and face the possibilities of injury, she wrote of Jadallah one of the three Palestinian brothers photographers being injured four times through his work, and she reported on the more tragically still, funerals they have to cover that is often involve friends and relatives. Smyth argues that their intimate knowledge of Gaza that allowed the brothers to take photographs different to those of Western photographers based in the area. Sure if you are part of a place you would see things differently because you are not only doing your job, you are affected by what you are trying to capture from another angle, you are not totally independent of your emotions.

Eman like almost all other Palestinian photojournalists could not get official training so she was trained as an individual by several photojournalists, and she had to convince her community that photography was only ‘just a hobby, not a lifetime career’ to escape more scrutiny. She had worked for different agencies for free just to have her pictures published.

Unlike Eman, Enas Mraih another Palestinian female photojournalist she was lucky to work with Alhadath newspaper published in Palestinian territories occupied 1948 called now ‘Israel’. She was invited to Denmark to participate in a workshop with 28 other journalists from 6 countries: Egypt, Jordan, Yemen, Occupied Palestinian territories of 1967, Besides Israel and the country host. Enas was even chosen to be on the cover of ‘Crossing Borders’ a magazine published in Denmark and circulated in the Arab world. Enas was accompanied by another two Palestinian women photojournalists; they were Kholoud Masalhah, and Qamar Thaher. Enas was more fortunate than other female Palestinian photojournalists in being able to participate few times in conferences to discuss the Palestinian Israeli conflict, and the struggle of Palestinians fighting for the right to be treated equally like Jewish citizens living in the same state holding the same Citizenship, but still suffer racial discrimination by the Israeli government for being Israeli Arabs.

Laila Abu Odeh is another female photojournalist working in Rafah who was a victim of aggression by Israeli forces; she was shot in her thigh by the Israeli soldiers while filming the destruction caused by the Israeli shelling of The Rafah Camp near Salah Eddin Gate on the 20th of April 2001.

Palestinian women started taking pictures of families and holy places, ceremonies and weddings because this was part of every day life, but ended up taking pictures of bodies of killed young children, shelled schools and homes, and lots of blood including their own for the same reason. Having been living in an area where everything is disputed including the rights of journalists, there are no institutions those women can request assistance from for training or protection. They are women armed with cameras chasing the truth no matter what the consequences are. Some of them end up in jail like Isra’a el-Amarna the photojournalist from Dheisheh refugee camp who has been detained by the Israeli occupation authorities. Isra’a was working in photography to support her poor family when the Israeli occupation authorities arrested her on accusation of membership to Qassam Brigades, and that she had the intention to carry out a martyrdom operation. A camera is as powerful as a gun but those who use cameras are not the coward ones.

Bibliography

Katz, Lee M. (2000) Life, limb, & a deadline to meet Editor & Publisher 11/20/2000, Vol. 133 Issue 47, p14

Hallote, R. (2007) Photography The American Contribution To Early Biblical Archaeology 1870-1920. Near Eastern Archaeology 70 no1 pp 26-41

Tamimi, I. (2008) The Palestinian Kulthum Odeh (1892 -1965) the first woman to hold the professor title in the Arab world, London Progressive Journal. Issue 41 October 2008

Mrowat. A (2007) Karimeh Abbud: Early Woman Photographer (1896-1955) Jerusalem Quarterly (Institute of Jerusalem Studies) Issue 31: p. 72-78

Mrowat, A (2007) Photography As Ethnographic History. Depiction of Israeli-Palestinian Conflict since 1948, The Institute of Jerusalem Studies.

Nassar, I. (2006) Familial Snapshots: Representing Palestine in the Work of the First Local Photographers History & Memory – Volume 18, Number 2, Fall/Winter 2006, pp. 139-155 Indiana University Press.

Ankori. G. (2006) Palestinian Art Reaction Books, London P36

Mohammed, E. (2008) Proud with no pride of the “me” I choose to be Voices from the Frontline. Available online at: http://www.peacexpeace.org/content/en/yourstory/write?memoir=148&showhidden=hb8fea1a312984aae10183bef02bd1f26 accessed 20/1/2009

Crager, J. (2005) See it now American Photo v. 16 no. 5 (September/October 2005) p. 10, 12

Burgess, N. (1994) Going Dutch British Journal of Photography v. 141 (June 8 1994) p. 20-2

Smyth, D. (2005) Funeral days British Journal of Photography v. 152 (September 7 2005) p. 12-14